Provenance n: where something originated or was nurtured in its early existence. – courtesy dictionary.com

Ask any knowledgeable automobile collector, restorer, auctioneer, or historian about what makes a car significant–and valuable–and they’ll tell you it’s all about provenance: knowing when a car was built, where, by whom, and to what specification. Originality, condition, celebrity ownership, race history, and the like can also come into play. Rare, historically significant cars with the most interesting, well-documented provenance are the ones that big-game collectors seek.

The waters get murky when a car’s provenance becomes compromised. Take, for example, two Jaguar D-Types both claiming to be serial number so-and-so. Or when a car’s body and chassis are separated — Along the way, the former gets mated to a new chassis, and someone else builds new coachwork for the original frame. One car is now two, but which is the “real” one?

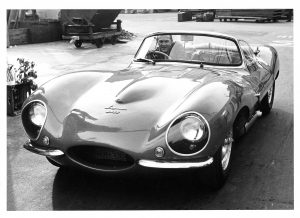

This is Steve McQueen in his very genuine XK-SS. Think he’d buy and drive a clone? Not a chance in my book…

Descending the provenance ladder one more rung takes us to the notion of “continuation” cars, an innovative term that describes new cars built to resemble the originals (or modernized versions thereof), purportedly picking up where production left off, however long ago that was. Some are beautifully done; some are junk. Some are so faithfully reproduced they’ve been passed off and sold as the real thing, which is called a felony.

I have considerable respect for the tenets of history, provenance, authenticity and originality. Which is why I gasped a few years back when someone shelled out $550,800 for a Mustang now dubbed a “genuine continuation Shelby GT500E” at a Barrett-Jackson auction. Startling, to say the least, as you can buy an authentic, 100-point 1968 Shelby GT500 KR for far less.

Shelby Licensing had given Texas’ Unique Performance, a deal to build “genuine continuation-series Shelby” Mustangs that resemble restomoded 1965-1968 GT350s and 500s. Unique bought used 1965-1968 donor cars, striped them down, and rebuilt them using a variety of aftermarket parts, Shelby and otherwise. A new Shelby number plate was affixed, although legally, these Mustangs retained their original Ford VIN. Thankfully this sham process is over.

Cuvee vi Dom Perignon has been produced to the strictest quality standards for hundreds of years in and only in Champagne, France. What if the company decided to throw its champagne-making legacy out the window, buy some 35-year-old juice from a wholesale grower in Nebraska, and hire a producer in Sri Lanka to bottle this stuff? Could it then slap on that legendary label and legitimately call it Dom?

Of course not. So how, then, can a 50+-year-old, originally six-cylinder powered used car become a new Shelby Mustang, continuation or otherwise? It can’t. Because in the time/space continuum we live in, history cannot be recreated at a later date.

Nothing’s wrong with clones, restomodifieds, street rods, or reproductions–as long as they’re represented accordingly and not wearing the false patina of a sprayed-on provenance. If you feel otherwise, then sample some of the mythical bubbly liquid made of 35-year-old Nebraska grape juice bottled in Sri Lanka (vintage-dated last Tuesday) and tell me if it tastes like Dom Perignon.