Only the largest, grandest and most historic factory property would do for Preston Tucker’s Car of Tomorrow

Photos courtesy of The Petersen Automotive Museum and Fiat Chrysler Archive

Everyone has (at least one) opinion about Preston Tucker and his near mythical Tucker 48 automobile. Some believe that Tucker was at least a huckster if not an out and out crook; intending to raise millions in a Ponzi scheme, then evaporate into the night with the loot. Others feel he was a visionary who conceived and ultimately built several dozen examples of a car so far superior to anything else on the road in the late 1940s, that the “Detroit Big Three” feared the competition, and conspired to put him out of business before he ever really got started. Others still, believe he simply bit off more than he could chew with such a monumental venture, never having the financial backing and gravitas to pull it off.

If you’re not familiar with the Tucker, it’s a story worth knowing and reading up on, as 2018 marks its 70th anniversary. Preston Tucker did many things in his very short life. Wikipedia defines him thus: “Preston Thomas Tucker (September 21, 1903 – December 26, 1956,) was an American automobile designer and entrepreneur. He is most remembered for his 1948 Tucker Sedan (known as the “Tucker ’48” and initially nicknamed the “Tucker Torpedo”), an automobile which introduced many features that have since become widely used in modern cars. Production of the Tucker ’48 was shut down amidst scandal and controversial accusations of stock fraud on March 3, 1949. The 1988 movie Tucker: The Man and His Dream is based on Tucker’s spirit and the saga surrounding the car’s production.”

These elegantly dressed models demonstrate the cargo space in the “frunk” because of course, the engine is mounted in the back.

Tucker, if nothing else, dreamed big. His gargantuan goal was simple; to design, develop, and produce the greatest ever and most advanced American automobile, named after who but himself. The car itself was a dazzler; with an aggressively elegant, and modern somewhat space aged design, offering superlative performance from its rear mounted, rear-wheel drive aircraft-derived liquid cooled horizontally opposed six-cylinder engine, encompassing a variety of safety features including its front center mounted “cyclops eye” headlight which turned left and right in unison with the steering wheel, a windshield designed not to break but to “pop out” forward and whole during the impact of a crash, and myriad other vehicle design and engineering advancements. Many of his original ideas for the Torpedo later showed up in other carmakers’ products, such as a torque converter drive for automatic transmission equipped cars, fuel injection, disc brakes, and other innovations we today take for granted on nearly any vehicle.

The conception and construction of such a grand machine mandated a headquarters and factory property that matched the car’s – and the carmaker’s – level of pizazz. Preston Tucker was at minimum, a superb promoter, quite the showman, and marketer of himself, and his company. However the story of what became the Tucker HQ and production factory predated the Tucker Torpedo by a half dozen years.

America believed that WWII would be fought and won in the air, and thus needed bombers and fighter planes by the thousands. Automakers weren’t building cars during those war years, but obviously had considerable experience producing motorized vehicles. So Chrysler won a contract to produce the Boeing B-29 “Superfortress” bomber, and needed an epically sized facility in which to build up to 1000 a month of them. The B-29 was a large aircraft, with a wingspan of 141 feet, a tail height of nearly 30 feet, and a gross weight of 140,000 pounds; so lots of ground space, and many many acres of covered, enclosed climate controlled factory production space, was needed. There was no existing building or factory anywhere in America that met those requirements, so the Army Air Corps commissioned a plan to scratch build it from a “green field” site.

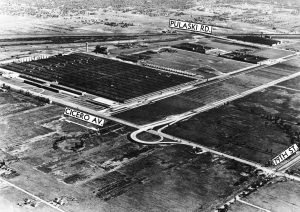

Architect Albert Kahn and his company were engaged to design and lay out the facility, with the George A. Fuller construction company retained as general contractor. Chicago was selected as the prime search area for a suitable site, logical enough given its closeness to Chrysler’s home near Detroit, and relative proximity to the Pentagon. Plus Chicago offered millions of acres of flat and vacant land, and a large work force ready willing and able to build the planes. Kahn and company designed a 19 building structure complex that would fit on the property ultimately chosen, taking up nearly 30 blocks of Southwest downtown Chicago, fronting Cicero Avenue at 76th street. Construction began in 1942, with the concrete, steel and wood buildings covering more than six million square feet, that’s nearly 140 acres of factory and office floor under roof. Which means that Chicago’s historic Soldier Field stadium, would fit inside the so named “Dodge-Chicago” factory buildings more than 20 times over. It was the world’s largest building at the time. There were also miles of underground tunnels to facilitate foot traffic, and the facility earned its own railroad stop. The plant also contained 7000 miles of water and sewer piping, and some 15 miles of electrical cabling.

It’s important to mention that Dodge-Chicago wasn’t just an assembly plant; it was a factory in the purest sense in that raw materials went in one end, and completed aircraft rolled out the other. Very few but highly specialized components or systems were produced by outside suppliers; this place built airplanes, just about from scratch. This included the B-29’s all-important Wright R-3350 radial 18-cylinder engine, which produced around 2200 horsepower; each B-29 ran four of them. The engine production schedule meant that each plane was allocated five engines (four for each build, and one for a spare). The city-sized factory, completed in 1944, employed approximately 17000 people at full capacity (in the best “Rosey the Riveter” spirit, nearly three-quarters of the plant’s line workers were women), and over time, along with other locales such as Boeing’s Kansas City factory, produced about 4000 B-29s. The Superfortress was America’s front line bomber during the latter years of WWII, remaining in active military service through the late 1950s.

At the end of WWII, no more new B-29 production was required. The plant was stripped, with much of the machine equipment sold off as “military surplus” and the rest of the massive buildings were emptied. Just in time for Mr. Tucker to come along and negotiate a lease (with the intent to purchase) agreement for the factory and office space needed to develop and produce his car.

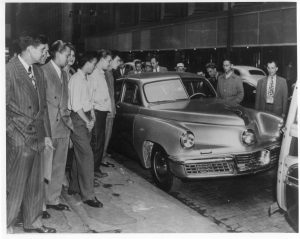

Tucker went about equipping and setting up the plant as quickly as he could raise the money to do so. The first Tucker prototype, dubbed the “Tin Goose” was built there, as were the 51 or so “production” Tuckers. This was also the locale for the famous Tucker christening party where factory workers struggled to get the under engineered, overweight Tin Goose running long enough for it to drive onto a stage where the Tucker family stood, as Tucker’s daughter famously crashed the nose of the car with a champagne bottle; the giant room filled with thousands of media, dealers, prospective investors, and factory employees witnessing the birth of Tucker the car and company.

Almost from the beginning, Tucker (man and company) were hampered by lawsuits and a variety of SEC investigations espousing all manner of criminal and business wrongdoing. Even though Tucker was acquitted by the courts of all charges, he was out of time and money, his heart and his spirit broken, by early 1949. Tucker, the car and the company, were shuttered and the massive Dodge-Chicago/Tucker factory went silent again. Preston Tucker still loved cars, and continued to hold out hope of re-entering the car business, only to die of cancer in 1953 at the age of just 53.

Post Tucker, the Dodge-Chicago facility was taken over by the Ford Motor Company. Later a portion of the property not being used was leased to the Tootsie Roll Company for the production of its famous chewy chocolate candy. Post Ford Motor and Tootsie Roll, the property was completely remodeled into a massive shopping complex, today called the Ford City Mall. The place is hardly the same, but the automotive roots remain.

For more on the Tucker story, I recommend The Indomitable Tin Goose, by Charles T. Pearson, and the just released PRESTON TUCKER and His Battle to Build the Car of Tomorrow, by Steve Lehto.